|

5. Prophecy of Doom It was Christmas, 1637, and the winter which was beginning brought calm and peace to the Jesuits at Ossosane. Father de Brébeuf, kneeling in the dark chapel, was counting the blessings God had bestowed on them, and they all began with Joseph Chiwatenwa. Thanks to Joseph, Teondechoren's slanders against baptism were having little effect. More than that, his cabin had become a Christian home. Most of the relatives living under the same roof had been baptized and were living good moral lives, including his brother Saoekbata, now called Peter. Joseph spent all his spare time learning to read and write, thus influencing his neighbors. Thanks to him, the Jesuits now had classes in their residence for the boys and girls of the village, and the classes were growing in number all the time. Thanks to Joseph, Echon was now able to write sermons which would appeal to the Huron mind. Joseph spoke so clearly that with his help Echon revised his book on the Huron language and grammar. Thanks to Joseph, who would be a perfect assistant, Echon could now plan to hold public instruction for the men of Ossosane. Jean de Brébeuf raised his huge form to a standing position. His heart was so full of joy and happiness at that moment, that his thoughts burst into words. "What shall I return to You, Jesus, my Lord, for all You have given to me? Your chalice I shall accept. Therefore, I vow in Your presence, to offer myself to die joyfully for You, if You decide I am worthy -of the grace of martyrdom. I will repeat this vow every day of my life." Deep within him Father de Brébeuf felt a strange assurance that someday he would fulfill that vow. The plans for public instruction of the adults of Ossosane had to be delayed until January. The fishing had been so successful that the village was busy with continued feasting for almost a month. It was Joseph's idea to carry out the instructions in dialogue instead of straight sermons. He would be the questioner; his strategy would be to act as an objector, or to pretend ignorance of the Christian truths. In this way, both he and Echon could do much preaching in an entertaining and thus more effective way. Father de Brébeuf found that the more he saw of his Christian Joseph and worked with him, the more he wondered at the marvel of God's ways. This man, not long before a savage, now lived a truly spiritual life, kneeling in chapel daily for prayer, meditation, and examen of conscience. He never began a day without asking the help of the Holy Ghost, and had become in every sense of the word a lay catechist. Since he was so much respected for his brilliant mind, Joseph was attracting great numbers to see the truth of the Faith. Whether they would accept Christianity strongly enough to live the Faith by obeying the commandments was a question only time would answer. The first adult to follow the good example of those in Joseph's cabin was his elderly friend who took the name Rene. By the middle of winter in early 1638, all of Ossosane was excitedly talking about the God of the Blackrobes. The chiefs of the village called a council at which Joseph, Rene and Echon were present. "We have listened well to what you have said," proclaimed the Captain, after all were settled with their pipes. "It is our decision that the people of Ossosane should believe the Blackrobes and accept their God." "Haau, haau, haau," resounded the cries of approval. The Captain continued. "Echon is to be raised to a chief of the Bears with the right to call a council." Joseph looked at Jean de Brébeuf. "It is a great honor, Echon, but I am afraid that their decision to believe in God is hasty and they will go back to the old ways. They will not give up their dreams and sorcerers so easily." Echon nodded. "I know, Joseph," and he recalled that just that morning, stones had been buried against the door of the Jesuit residence. It was a surprise to the priests at Ossosane to see Isaac Jogues arrive at their cabin, tired and dusty from his twelve-mile walk from his northern border village. "All our efforts to Christianize the people of our village have been fruitless. Father," he said to De Brébeuf, explaining his unexpected visit. "Except for Pierre, who is not only faithful but saintly, and a few prospective converts, we cannot claim any real results. The sickness caused so many to die that there are very few people left. Perhaps if Father Pijart and I could be sent to another village--" Father de Brébeuf thought for a moment. "I have talked with Joseph," he began. "We should have a mission at the capital of the Cord nation. This village is more populous than Ossosane. The Cord chiefs have even more power than the Bears." He hesitated. "If we could gain influence among the Cords as we have among the Bears at Ossosane, we might then gain all the Hurons for God." Father Jogues spoke up quickly. "But the Cord nation is so hostile. They even planned to kill you once, remember? Send me. Father, and then if I return alive, you will know if they are friendly yet or not." The superior of the Huron missions smiled. "A general leads his army, my son. He does not follow it." Jean de Brébeuf and Joseph Chiwatenwa left for the Cord capital in early April. They walked across mostly level land, crossed the Wye River, passed many small villages, and enjoyed the scenery of the lakes that lay between them and their destination. The capital of the Cords was a fortified village, built in the same manner as Ossosane. Father de Bre-beuf knew that the relatives of a Christian Indian he had known in Quebec, Louis Amantacha, lived here, and he and Joseph visited them first. After the usual courtesies were over, Echon said, "The Blackrobes would like to have a cabin in the chief village of the Cords." The word spread all over the village immediately, and an old chief soon presented himself to Father de Brébeuf. He wore a loose beaver skin over his shoulders like a mantle, and his greased hair was the color of gray stone. "I am Ondihorrea. My people do not want the Blackrobes here." "I am a Bear chief," proclaimed Echon, standing his full height and looking down on the old man. "I request a council." Ondihorrea shrugged. The council was called a few weeks later, and when it appeared that the answer was going to be no. Father de Brébeuf spoke out. "If you have Frenchmen living in your village, you will be in a much better position to trade with the French at Three Rivers." The chiefs mumbled among themselves, but Echon's argument was sound. Unexpectedly, they decided, "You may come to our village, but we will not build a cabin for you. There is an empty cabin you may use." Father de Brébeuf looked at Joseph. "They might change their minds. Let's take possession right away," he whispered, smiling. Echon and Joseph followed the chief who agreed to lead them to the cabin. When they saw it, Joseph walked back and forth around it several times. He grunted. "No wonder they offered you the cabin. It is about to collapse! It is broken from neglect and the weather. It is small and dark and damp. No Huron would hve in this!" De Brébeuf agreed. "We'll send some of the French workmen to repair it. Father Jogues and Father Chastellain will start the mission here." He became quiet and pensive. As if from far away, he heard Joseph's voice. "They will live poorly, like our Saviour, who was born in a lodge of broken bark in the moon of wintertime." There was always great excitement in the Jesuit residence when one of their brothers in Christ walked stiffly and haltingly up the beach below Ossosane after the long, hard journey from Quebec. The priests at Ossosane gave a rousing welcome to the newcomer who arrived on August 26, 1638, with a young French companion. Father Jerome Lalement was talkative and enthusiastic. "The trip took twenty-six days from Quebec. It is amazing how these bark canoes skim over the top of the water. Really, they are more like bark cradles!" The priests laughed loudly. Father de Brébeuf asked, "Did you meet with danger?" "Only at one point. We stopped at one of the small islands and an Algonquin Indian tried to strangle me with a leather string. One of his children had died after a French surgeon bled him, and he wanted revenge by taking the life of a Frenchman." The talk turned to happier news from home, their beloved France. Later, each priest started to the chapel to reminisce in his private heart and renew his gift of self to God. Father Lalement put his hand out to touch the arm of Father de Brébeuf. "Jean, I must speak to you privately." Father de Brébeuf nodded. Father Lalement took out an envelope from the breast pocket concealed inside his robe. He held it motionless for a moment, statue-like as the cabin fire outlined his lean face and large brown eyes and thick dark hair smoothly combed back from his forehead. Then he handed it to Father de Brébeuf. The rugged giant of the Huron mission took out the documents contained in the envelope. After he read the first letter, he fell to his knees before Father Lalement. His voice was low but steady. "I have often begged for someone holier and wiser to replace me as superior of the Huron mission in these past four years. I pledge my obedience to you and I turn to you all authority over all the priests and workmen, over all the material things, and over the spiritual apostolate." Jean de Brébeuf felt a tightening in his throat, and momentarily weakening in his usual calm control, he blurted the one question which was important to him, "Am I ordered to go to Quebec--or have I been permitted to remain among my Hurons?" Jerome Lalement's eyes filled with tears. "Do you think that anyone could take the place of Echon? You are to stay, naturellement. This is confirmed in the other letter in that envelope signed by our superior in Quebec, Father Le Jeune." Jean de Brébeuf's mouth trembled, and his great body felt weak from gratitude and relief. His eyes which glowed like embers from the cabin fire were alive with genuine joy. "Father, believe me, I am so grateful to be relieved of this great responsibility. I have always felt that I was not one to give directions. I need someone to obey and someone to rely on." Lalement shook his head. "You are a humble man, Jean. It is I who shall rely on you. I have read every Relation sent back to France from the missionaries. You were my inspiration. 'If only I could be like Jean de Brébeuf,' that has been my wish." His tone of voice grew higher with excitement. "I have plans, Jean. First we shall find a beautiful and practical location, and then we are going to build a permanent residence there--in the French style. This will be our central headquarters. I have even picked out a name. Sainte Marie-among-the-Hurons. From Sainte Marie, our priests will be able to spread out and visit many villages." Jean de Brébeuf listened. This plan reversed his own program which had been to establish separate bark cabins, like those of the Indians, for the missionaries in each village. "I have felt strongly that it was important that we win the trust of the natives by becoming one of them as far as we are able." He spoke hesitatingly as he drew a mat close to the fire to resume a sitting position. Perhaps he was speaking out of turn. "But, Jean," said Father Lalement, "because we are missionaries, this does not mean that we can relax the strict observance of our religious discipline. If we have a central residence, we can live the life of a Jesuit almost in the same manner as we did in France." Jean de Brébeuf nodded, accepting the order of the new superior. Lalement went on. "I have another idea, Jean. You have had French workmen here, but I dream of having helpers with more apostolic motives. If we had men who sincerely desired to serve God in close union with our priests of the Society, but who did not wish to take religious vows, think of how much more profitable spiritually our work would be! These men would give themselves to God for a time. I would call them donnes or oblates." "The young man who came with you?" "Yes, he is a donne, Robert Le Coq. Our Provincial in France, and Father Le Jeune at Quebec both were in favor. They will send us the young men who volunteer to be donnes." Father de Brébeuf gazed into the fire, nodding slowly in thought. "Men of high principle, living in chastity--they would be truly apostles." He turned his head to face Father Lalement. "Father, it is an excellent idea." "The first thing we must do, Jean, is take a census. "Fine. I know well where all the villages are located and how many cabins and families are in each village--1 will write it down for you." "No, Jean, I mean a new census taken on the spot and by actual count." Jean de Brébeuf nodded. He smiled broadly. "You see. Father, how wise it is that you will be in charge. I never had a head for accurate figures, or organization. "Echon, Echon," whispered Lalement. "For your heart and spirit, I would gladly trade my ability for organization." Joseph Chiwatenwa was the first of the believers to hear the news that another Blackrobe was now greater than Echon. Very early in the morning he ran to the residence, La Conception. He saw Father Le Mercier working in the little garden nearby where the priests grew grain for the making of the Communion hosts. Joseph went over to him. "No one could be above Echon," he protested to Father Francois. "He is one of us. He thinks like the Huron, and he speaks our council language like the finest of our orators. And who has the body and endurance of Echon? Who has his wisdom and courage? I look at Echon and I say, 'If a man can love so greatly, how much more so does God love!' " Father Francois placed his hand on Joseph's shoulder. "Think of us, Joseph. The priests here have molded themselves according to Echon's spirit. Sometimes at night I have awakened and there I see Echon kneeling on his mat in prayer. I pretend to be asleep, but I see, too, how he causes pain to his body to suffer more for God." Father Francois looked back at the growing stalks of grain. "Yet, we love our new superior. We knew him well in France. He is a man of great brilliance and goodness. He is the same age as Echon, but has been in the Society of Jesus seven years longer. Don't worry, Joseph, you will learn to admire and love him as we do." "Where will Echon go?" "He is preparing to leave today for the chief village of the Cords. He has been bursting with the anticipation of the work to be done there." Father Francois bent and pulled out a weed. "Fathers Jogues and Ragueneau will be so happy to have Echon with them." Joseph said good-by to Father Le Mercier and walked quickly to the residence. "Echon!" he called. Father de Brébeuf looked refreshed and exhilarated. "Joseph," he smiled. "I am going to leave for a while." "Echon, things are unsettled in the capital of the Cords. There are war cries in that village. They are closer to the Iroquois. The village might not be safe." "Then I must hurry, Joseph, for we have two priests there." "I will go with you." Jean de Brébeuf and Joseph Chiwatenwa walked the familiar route to the Cord nation once more. As they neared the capital village, there was the sight and sound of confusion all around. Piercing shrieks of "wiewiewiewie," the war cry of the Hurons, filled the village and its surrounding area. The warriors, painted boldly and wildly, slammed their feet down in the passionate war dance. Then armed with tomahawks, knives, spears, clubs, and bows and arrows, the painted braves banded to begin their search for prisoners along the trails toward the Iroquois.

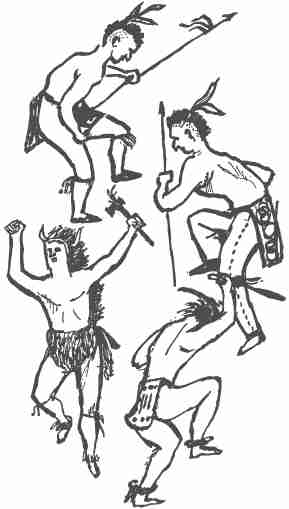

The warriors began the bloodcurdling, war dance

The priest and the believer went to the small cabin which housed Father Jogues and Father Ragueneau. There they heard startling news. "The Iroquois are unfriendly. They are slowly but surely advancing into Huron territory. The rumor is that the tribes of the Iroquois are merging for strength. It is also rumored that the Dutch, who are so hostile to the French, are supplying them with arms, hoping to win their friendship and thus make them, too, the enemies of the French." The news shook Jean de Brébeuf. His enthusiasm of the morning before was all but gone. A few days later, the cries of victory, which meant that prisoners had been captured, could be heard in the distance. Immediately, the villagers went wild with glee. They began making fires in the field outside of the village, and everyone, even the women and children, collected hatchets, arrows, pothooks and knives to be used for the torture. The band of Huron braves of the Cord nation, raving triumphantly, ushered their prisoners into their village. Father de Brébeuf counted twelve Iroquois with porcelain collars on their necks to mark them as prisoners. Their bodies were blood-caked from some of the preliminary torture they had undergone. The whole village greeted the prisoners with "caresses," the term given to the custom of touching red-hot arrow points and hatchets to the bodies of the captives as they passed through their midst to the open field outside. It sent chills down the back of Jean de Brébeuf when he saw the delight shown by the women and children as they inflicted pain on the prisoners. The noise was deafening, and now and then over the din, the order to "sing" came through clearly. The Iroquois prisoners were forced to dance and sing, proclaiming how happy they were. The three priests, with Joseph by their side, forced their way to the front row of spectators. By now burning fires had been lit in a long row. "Walk!" screamed a Huron streaked with red and black war paint. One by one the prisoners were made to walk back and forth on the glowing fires. The children crawled on their stomachs, with spears in their hands, and jabbed at the prisoners' legs as they walked or danced, according to the order, through the fires. After this ordeal, the captives fell to the ground, howling their defiance, and Jean de Brébeuf gave a nod to his companions as he saw that the first few prisoners were temporarily ignored on the side lines. Since all the Hurons were watching the victim now walking the fires, the missionaries slipped unnoticed to these prisoners who half lay, half sat, their feet and legs becoming a raw and swollen mass of blisters. "Listen to me, my brothers," whispered Father de Brébeuf. Their hostile eyes showed that the Iroquois prisoners mistrusted this strange-looking giant in the black robe, but as he talked on, they began to listen. "Your pains will soon be over, but what will happen after your death when you go to the Land of Souls? If you listen to me and do as I say, you will find a paradise in the Land of Souls." The eyes of the Iroquois showed that they were interested. All during the night the tortures went on, but, at every moment of rest, one of the priests, or Joseph, would go to the half-dead prisoner and instruct him. There was one who caught Echon's attention more than all the others. He had identified himself, saying, "I am Ononkwaia, a chief of the Oneidas." One of the first to listen to Father de Brébeuf, his interest was intense. As morning broke through the darkened sky, the natives picked off the prisoners one by one, scalped them and crashed in their heads. Jean de Brébeuf prayed for them one by one. Without the Hurons being aware of it, he and Fathers Jogues and Ragueneau, with Joseph's help, had stealthily managed to win the free consent of the victims and had baptized them. The Oneida chief, the bravest and most important of the prisoners, had been saved for the last and greatest torture. Before the Hurons came to the place where he lay shackled to the earth, Echon spoke again to him. "You have heard me talk a great deal now about our Father in heaven. Do you believe?" The Oneida chief looked steadfastly into Echon's face. "Echon, I believe. Baptize me!" Joseph handed a bark bowl containing water to Echon. The priest poured the water over the head of the suffering man as he said, "Peter, I baptize thee in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost." A scream broke the peace of the moment. Rushing across the narrow field which was littered with smoking ashes, bloody weapons and pieces of blackened flesh, came a warrior who wore his hair in high ridges clipped from his forehead to the nape of his neck. He was painted in red and black, and his body was spotted with caked blood. He grabbed Echon, who was still kneeling, and roughly pushed him against the outer wooden palisades of the village. "Your baptism!" he shouted. "You say it is to make one happy after death!" His voice was shrill enough to attract the attention of the other men who were building a platform near some new hot glowing fires where the Oneida chief would be paraded and tortured once more. A menacing crowd began to gather around Echon. Joseph spoke loudly. "Why do you become angry over things you do not even believe in?" Quick as an arrow this answer came: "If you try to talk to the prisoner again, we will split your heads." The painted Hurons unshackled the Oneida chief, whose body was already mutilated and blistered, and they pushed him along till he reached the platform and climbed on to it. There the final burning of the prisoner began. Some of the Hurons on the platform with him shoved burning torches into him. Others poked the torches up through the poles which supported the platform. Suddenly, with shocking strength and speed. Peter grabbed one of the burning torches and attacked the Hurons. The noise of bedlam surrounded the scene. The platform sparked with fire as the Oneida chief fought wildly. The screams grew louder as Peter missed his footing and fell. A group of braves picked him up bodily and threw him on the fires. Echon prayed for his new Christian as he controlled his nausea at the sight and sounds and smell of burning flesh. "He is a devil," cried a squaw. Father de Brébeuf stared unbelievingly. Peter had leaped from the fire, and covered with burning coals, still was attacking the Hurons with the torch he held. The villagers were becoming hysterical. This was unheard of. One of the braver Hurons hit the prisoner with a club. Peter fell, and another Huron dashed over to him and chopped off his hands and feet. Still he wriggled and struggled free. The villagers gasped as one voice, and then there was a sudden silence. The Oneida chief, without hands and feet and blackened from the fires, was crawling toward them on his elbows and knees, his eyes burning like fires from another world. The squaws and the children, and even most of the braves retreated, so deathly afraid were they of this specter. With a yell, one of the Hurons leaped forward, and cut off the head of the Oneida chief. He cupped his hands to hold some of the gushing blood, and drank it to receive courage such as this man had. The triumphant cries had faded, and the wails of the squaws took over. Never had the nation of the Cords seen such courage. This was a bad sign. This meant doom for the Hurons! The Iroquois would be victorious against them. It was foretold by this omen. In the midst of the moaning and spoken fears, the warrior with the ridges of hair who had caught Echon in the act of baptizing Peter yelled for silence. "The Oneida chief had more than human courage. It is because Echon--the sorcerer--told him to defy us and he would give him heaven after death!" While the villagers listened to him, the missionaries quietly went back to their small cabin. This new accusation would mean more trouble, more distrust. Yet, in his heart, Jean de Brébeuf could not put a damper on his joy, for he felt that Peter, the brave spirit, now enjoyed the freedom of the children of God in heaven. But what about the Hurons? Echon could not shake off a sudden feeling that the clouds of doom had indeed settled over the People-of-One-Land-Apart.

|