9. The Rescuer The news of the decision of the council of the great chiefs of the Huron nations struck the few Christians at Ossosane with fear and dismay. Joseph Chiwatenwa paced around the fire in his cabin, glancing frequently at Marie Aonetta who was still so busy caring for the sick ones within their long-house. "There are priests in the villages of the Huron nations which have voted death, Marie Aonetta. They will be struck down without any warning." His voice was agitated. "I must go to them. Perhaps I shall be able to help them--maybe even save their lives!" Marie Aonetta stood and came over to her husband. "If you go, Chiwatenwa, you may never see our children again. For they may die, but you would not be here." Tears streamed down her dark face, and the strain of the hard days showed in her thinness. Her high cheekbones were accented by the slight hollows in her cheeks, and her eyes were large and luminous, like the embers of the cabin fires. The long dark braid had fallen over her shoulder and as he looked at his wife, Joseph felt she was both child and mother. She was a child in her simplicity and goodness, but a mother in her depths of suffering. "Even if I stay, I could not make them well. All the help I could give would be some slight comfort to you." Joseph took the long braid from Marie Aonetta's shoulder and affectionately placed it to fall along her back. "But in your heart, Aonetta, you know how I love all of you. You know how much it costs me to go away now. Yet, I would leave you in the hands of Our Father, and if you needed help. Father Le Mercier or Father Ragueneau would be here." Joseph's heart ached from the conflict within him between the love of God and His work which compelled him to leave, and the love of family which urged him to stay. Marie Aonetta's voice was low. "You must go. I know it in my heart. You have told me so often to trust Him who is the Master of all this. I shall do that, Chiwatenwa." She moved away silently and began packing into a leather pouch the corn meal cakes she had been preparing. "You must wear your heavy beaver robe, and wrap your feet in skins, for it is winter and the weather is cold." With wifely concern, Marie Aonetta began .searching the storage shelves under the cabin roof for rabbit skins. "You must take your snowshoes, too," she added. Joseph then knelt by the side of each of his three sons who were so sick. He asked God to watch over •them as he struggled with his natural feelings to stay and care for them himself. When he rose to say good-by to Marie Aonetta, Joseph could only look at her silently, pledging his love for all of them with his eyes. The route to the Tobacco nation was south and west along the shores of the great lake. He would go here first, for Father Jogues and Father Gamier were working in these villages. But before Joseph left the walls of Ossosane behind and ran down the cliff to the stony beach to begin his trip, he stopped first at the Jesuit residence. Here Father Ragueneau heard his confession and gave him .Holy Communion. It was Joseph's practice never to start on a journey without first arming his soul with the strength of the sacraments. The trip was long and lonely. By the second afternoon the sky darkened and snow began to fall steadily. Joseph's feet started to feel cold through the rabbit skin coverings, even though he was walking quickly. When it became too dark to see his way, Joseph decided to camp for the night. By this time, the forests and the beach were white and wet with soggy snow. Joseph managed to find a clump of trees with branches thick enough to catch the snow so that the ground below was fairly clear. He gathered some twigs for a fire and heated one of the corn meal cakes for his supper. Then Joseph made a bed of twigs, carefully covering his head and body with pieces of bark and fallen branches. He fell asleep, huddled this way on the frozen ground, fingering the rosary which had been Echon's gift to him. Before it was light, Joseph woke up from the painful cold which had seized upon his whole body. The weight of the snow in the tree branches above him had pushed its way through, and he had become covered with a blanket of snow sometime during the night. In order to increase the circulation in his body, Joseph stamped around the ground vigorously. He was hungry, but the corn meal cakes were frozen solid) and he could barely manage to break oS a few mouthfuls for his breakfast. As the first gray signs of morning broke through the dark sky, Joseph tied his snowshoes to his feet with strips of leather and continued on his way to the villages of the Tobacco nation to help Fathers Jogues and Gamier in their danger. The first village he came to was small and unprotected, merely a few cabins scattered in the fields. At least Joseph was given some food here, and the hospitality to dry and thaw out his frozen clothing. "I am looking for the Blackrobes," he said. "In which direction is the village where they are staying?" His hosts would not even mention the names of the Blackrobes. They merely pointed to the south. By early afternoon, Joseph came to a larger village. He walked around quietly, hoping to see a sign of the two priests. In a secluded spot on the edge of the village, Joseph noticed that a cabin had collapsed. Curiously, he walked closer, attracted by the pieces of wood, painted red, which lay in front of the tumbled cabin. They were remnants of the red cross which marked the cabins of the Jesuits! Feverishly, Joseph ran to the nearest cabin. "Where are the Blackrobes?" he shouted. The people within looked at him coldly and continued with what they were doing. One by one, each took a handful of fat and tobacco, threw it on the fire, and, while the blaze sparked and crackled, all chanted invocations, asking a certain demon to accept their homage. "Are they in this village?" Joseph persisted. "We have driven them away," a squaw screamed, and she picked up a blazing stick, threatening to burn Joseph Chiwatenwa. When he had searched the village and was satisfied that the missionaries were not there, Joseph went on to the next village. There were nine villages in this nation. He would find the two priests if he had to search all nine! By early nightfall, he could tell the next village was close by from the shadows and sparks of fires in the distance. Suddenly, he heard the threatening, howling cry of a band of braves stalking a prisoner. The sound grew louder and louder until he found himself in the midst of the tumult. Someone rushed him from behind, and Joseph fell face down into the snow, the heavy, warm weight of another man on top of him. "You are one of us!" his attacker said in a tone of surprise. "I could not tell in the darkness." The brave who had rushed at him roughly helped Joseph to his feet. By now the other braves had run close to them, and Joseph saw that they had painted faces and were armed with hatchets. "We left a feast to kill the Blackrobes. We drove them from our village only a short while ago. They must be in the forest." When wild braves are feasting, their heads light from tobacco, they will do anything for excitement, thought Joseph, searching his mind for a way to influence them. "It is getting too dark to find anyone. All you are doing is trampling in the snow and destroying their tracks. Go back and enjoy your feast." Joseph paused. One of the braves answered. "The stranger is right. Let us go back to the feast. We can follow their tracks in the morning." They headed back for the village, not noticing that Joseph fell behind. Now he was worried. If the missionaries were out here somewhere in this grove of fir trees, they would be in more danger from the cold. The Blackrobes would probably head west toward the next village, Joseph reasoned, and begging God's help, he began to move swiftly in that direction through the darkening night, the fierce wind beating at his face. When he thought it was safe, he began to call loudly, "Ondessonk!" It seemed useless, and then, finally, Joseph heard a hollow-toned voice, its echo lost in the absorbing snow. "Chiwatenwa--could it be possible? Is it you, Chiwatenwa?" Joseph's heart pounded and he thanked God as he came upon Father Jogues and Father Gamier sitting in the snow. Father Gamier, so young and ghostly pale in the darkness, half lay against a tree, his thin body shivering, with no protection but his black robe. "He is sick with a fever," said Father Jogues. "He is suffering more from hunger than from anything else." "How have you been treated?" Father Jogues smiled through his beard which glimmered from wet drops of melted snow. "We have suffered hunger, cold, snow, illness from malnutrition- we have been driven from cabin after cabin,despised by everyone. We have spoken of the Faith to over three hundred people, and not one--not one-- has been converted. And always the tomahawk is poised over our heads and we wait for it to strike, knowing that our blood will do more to convert these natives than our sweat. But God's will be done."

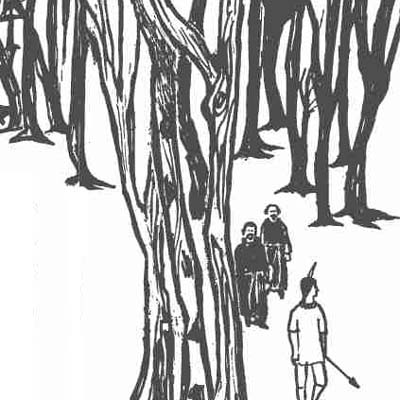

Joseph led the cold and starving priests out of the forest

The smile was still on the face of Isaac Jogues, and Joseph smiled in understanding of the love of God which could make a man happy even in his torture. "We must get back to the village, even though a band of braves is seeking to kill you. We have a chance in the village. Out here we shall die of exposure." They helped Father Gamier to his feet and walked the distance back to the village as swiftly as men who are starving and numb with freezing cold could walk. At the entrance of the first cabin they came to, Joseph pounded at the bark door and called for help. A squaw pushed aside the covering to let Joseph in. At that moment, she saw the two missionaries behind him. With a scream, she closed the entrance and shouted at them to go away. The same thing happened at the next two cabins. Joseph was becoming desperate, and then he remembered that some distant relatives of his lived in this village. After an inquiry, the three travelers made their way to the cabin of his relatives. The reception was hostile. "We have heard of you, Chiwatenwa--the believer!" Their tones were full of contempt and hatred. "You are a disgrace to the Hurons!" "We do not consider you our relative any longer!" Joseph listened to the abusive words silently, and then, still standing with the missionaries near the entrance of the cabin, he told them in a loud, clear voice: "You call me 'the believer.' You think you are cursing me; yet that is my greatest joy. As for you, your thoughts extend no further than this life--when it is life after death which is most important. You are blind because you want to kill the Blackrobes, who love you more than themselves, for their lives are less precious to them than your salvation!" Joseph's voice rang in the deathly quiet cabin, and the truth of his words softened the hearts of the Indians so that they at least offered hospitality to the three Christians. Joseph Chiwatenwa stayed with Fathers Jogues and Gamier until he was sure that the greatest danger had passed. He preached with them, boldly and bravely. While there appeared to be no good results, at least some of the people of the Tobacco nation became a little less hostile to the Blackrobes. In this same way, Joseph Chiwatenwa went on to protect Fathers Daniel and Chaumonot who were working in a village of the Rock nation. In February, 1640, the smallpox plague began to wane. The danger to the missionaries became less severe, probably because the Council vote of death had not been unanimous, and also because the Indians feared French reprisals if they killed Frenchmen. The following month, the missionaries gathered at Sainte Marie and told of their experiences. Each one--De Brébeuf and Chastellain from the capital of the Cord nation; Ragueneau and Le Mercier at Ossosane of the Bear nation; Jogues and Garnier with the Tobacco nation; and Daniel and Chaumonot with the Rock nation--each one had this to say: "If it had not been for the timely arrival of Joseph Chiwatenwa, we would have been badly maimed or killed. Our Joseph is truly an apostle to his people." Later, Father Jerome Lalement wrote to the superior in France: "He is the apostle of this country, existing only for the glory of God, having love only for Him. He has the qualities of an apostle, and has performed the office of one at the peril of his life. There is no place in all these regions in which we have set foot, where he has not boldly preached the greatness of Him whom they ought to adore as God, and the obligations under which we are to the Blood and to the Cross of Jesus Christ." It was so good to be home again, Joseph thought. His body was fatigued and badly in need of refreshment. Marie Aonetta, looking bright and happy, prepared the fire so that Joseph could take a sweat bath. "All who were sick in our cabin have recovered," she repeated happily. "They bear the deep marks of the disease on their faces, but they are well, and God has let us keep our sons." Joseph sat on the mat near the very hot fire. Marie sat a little distance away listening to the stories of the dangers Joseph had faced with the missionaries. Then she told him all the news. "My cousin was dying and her husband would not let her be baptized. I talked to him, and prayed, and finally, he consented." Joseph looked at his wife proudly. She loved the Faith as he did. "There is more, Joseph. Rene has remembered all your words. He has begged God to forgive him for going back to the old superstitions, and he is such a good Christian again." It was customary that when an Indian took a sweat, he spent the time in bragging about his own accomplishments. But as Joseph felt his pores open till he was perspiring freely, his thoughts were not on himself, but on God, and his prayer was a poem of gratitude and praise: Lord God, At last, then, I know Thee. Happily now I know Thee. It is Thou who has made this earth that we behold; And this Heaven that we behold; Thou has made us who call ourselves men. Just as we ourselves are masters of the canoe, Which we have made a canoe, And of the cabin, Which we have made a cabin, So, also, Thou art master, Thou, who has created us. A few weeks later, Joseph went fishing with his old friend Rene. It was a beautiful spring day and the air had the smell of lightly scented freshness. The fir trees were losing their dullness, and traces of green dotted the bushes and the ground. The sun became unusually warm in the afternoon, and after Joseph and Rene had a lunch of fresh fish cooked over an open fire, Joseph stretched out near a clump of bushes and fell asleep. A short time later, Joseph woke up suddenly, spontaneously sitting up and grabbing his knife. His hands were clenched, and his face set like a mask. "Chiwatenwa, what has happened?" Rene asked, concerned. Joseph stared at Rene unseeingly for a few minutes, and then he shook his head from side to side. "I had a dream--it seemed so real. I was attacked by two Indians and they were about to kill me." He put his knife back in his belt. Rene made a face of surprise. "If we were not Christians, Chiwatenwa, now you would make a feast, killing two dogs, since this is the remedy to protect yourself from danger." Joseph stood up. His dark eyes gazed calmly over the lake to the point where the puffy white clouds of the sky joined the water. "The dream is not the master of our lives. God is the master, and He will take care of us according to His good pleasure." The two Christian Indians went back to their canoe to continue fishing, but Joseph's mind was not on his work. He was struggling with two Indians, fighting hard for his life--the vision was so real that he could not shake it from his thoughts.

|